Part of Wimbledon’s timeless appeal is that the English country-garden aesthetic of lawn tennis competition in traditional form has been maintained while the tournament evolves in sync with the professionalisation of the sport.

From the arrival of vulcanised rubber (for tennis balls) and motorised lawn mowers (to trim the Perennial Ryegrass to the required 8mm) to IBM data analytics (readily available match stats on the My Wimbledon app) and Hawk-Eye (10 cameras on every court for challenge replays), modern innovations serve to enhance the traditional look and spirit of The Championships.

Today, for example, the officiating team is a thoroughly professional operation, with

377 officials working as chair umpires and line umpires (327), off-court staff (14)

and review officials (36). These officials preside over more than 650 matches played

during the Fortnight across 18 courts.

Dressed in elegant style with a nod to heritage, courtesy of Polo Ralph Lauren, the Official Outfitters to The Championships, officials resplendent in smart twill blazer, silk tie, striped shirt, chino trousers and tortoiseshell sunglasses are a key element of the optics.

Long gone are the days when lines were called by unpaid volunteers without official training and licence. Sixty years ago, a first-round match between the South African left-hander ‘Big' Abe Segal and the bespectacled Clark Graebner of the United States was deemed a snoozeathon – and that was no reflection on the entertaining standard of tennis.

According to The Wimbledon Compendium, one of the most notable events of the 1964

tournament was the match that ‘took place on a hot and sunny afternoon, just after

the annual umpires and line judges Championships’ cocktail party’.

Segal quickly romped to a straight-sets win. Victory was sealed when his American opponent hit the ball out. Both players rushed to the net for the congratulatory handshake. The only problem was that the last ball hadn’t been called ‘out’.

When eyeballs swivelled towards the line judge to query the silence, the reason was apparent: Dorothy Cavis Brown, dressed in cocktail party outfit of pearls and high heels, had slumped to her right, visibly asleep in her chair.

A ball boy was charged with trying to wake her up, but couldn’t rouse her. Segal himself

walked over and tapped her on the shoulder, whereupon she woke up and duly called

‘out’ so the match could be officially concluded. Segal went on to reach the quarter-finals.

And Mrs Cavis Brown? She was given a few days off from her duties.

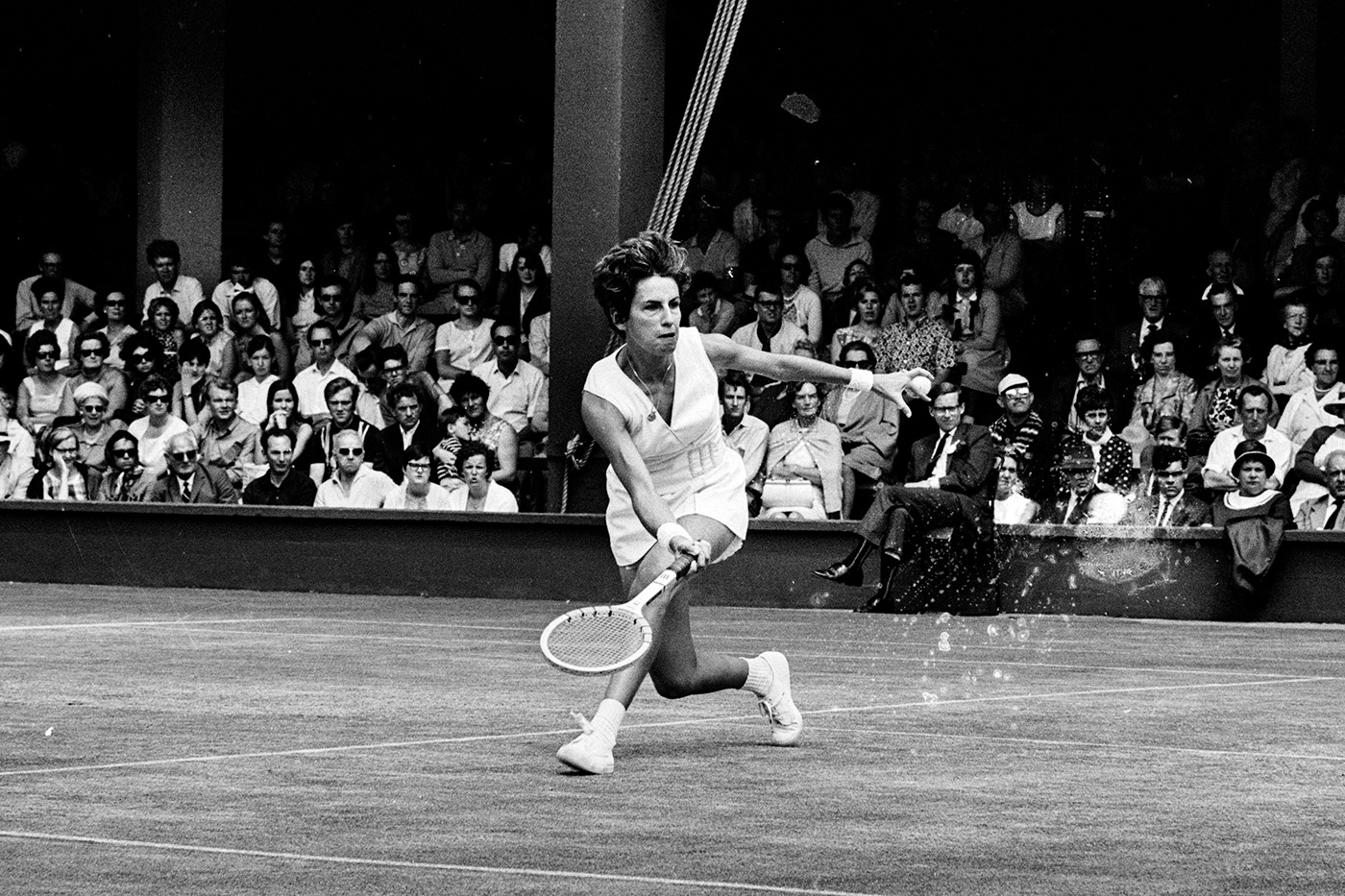

In retrospect, the 1964 tournament was also a milestone for Maria Bueno fans. This was the year that the supremely elegant Brazilian won her third and last ladies’ singles title, defeating Margaret Court in the final.

Bueno's style was mesmerising – a combination of aggressive net play, set up by rifled grounds strokes and a graceful athleticism around the court that often saw her likened to a prima ballerina.

"I know of many players, women and men, who admired Maria's game and took inspiration

from her beautiful style of play and her relentless drive to be a champion," Stan

Smith said when the Sao Paolo-born champion was inducted into the International Hall

of Fame in 1979.

Bueno also became a notable muse for the tennis dress designer Ted Tinling. Some of the bespoke garments he made for her line up in Tinling's own fashion hall of fame.

What she wore at The Championships became headline news. In 1962, one of her white outfits had an under-skirt and knickers in All England Club colours of purple and green; another featured hot-pink diamond adornments on the skirt lining.

In both cases, the ‘shocking’ elements of her outfit were only visible when she served. Only when she changed ends did spectators at the other end of the court understand what the initials gasps were all about.

The hot-pink moment was the final straw. The following year the All England Club made

it a condition of entry into The Championships that competitors were dressed ‘predominantly

in white’.