What a difference eight months have made in the life of Roger Federer. The last time we saw him in 2016, he was lying face down on Centre Court at Wimbledon, having tripped and injured his knee in a five-set, semi-final defeat to Milos Raonic. It was a rare fall, even on grass, for the infallible Swiss, and it seemed to sum up the struggles of a veteran champion trying in vain to defy time and the inevitable decline that comes with age.

In Indian Wells we heard less about 35, and more about another figure: 1. Suddenly, the No.1 ranking, which Federer hasn’t held since 2012, is within reach again. There’s a long way to go, obviously; just ask Djokovic, who won two majors and three Masters events in the first half of 2016 and still finished No.2. But it’s not too early to say that Federer has, for the moment, made himself the man to beat again.

How has he done it? According to Federer, you can start with his father, Robert, who urged him to, “Hit the backhand, dammit.” From there, you can look toward the man who has been Federer’s coach for since late 2015, Ivan Ljubicic. The former Top 5 player, and frequent Federer victim, had a muscular one-handed backhand, and you can see a little of it in the more free-swinging version of the shot that Federer is using this year.

He’s going to the slice less, taking the ball earlier, and extending through it more aggressively. The aggression in that shot has, in turn, has made Federer’s forays to the net more effective.

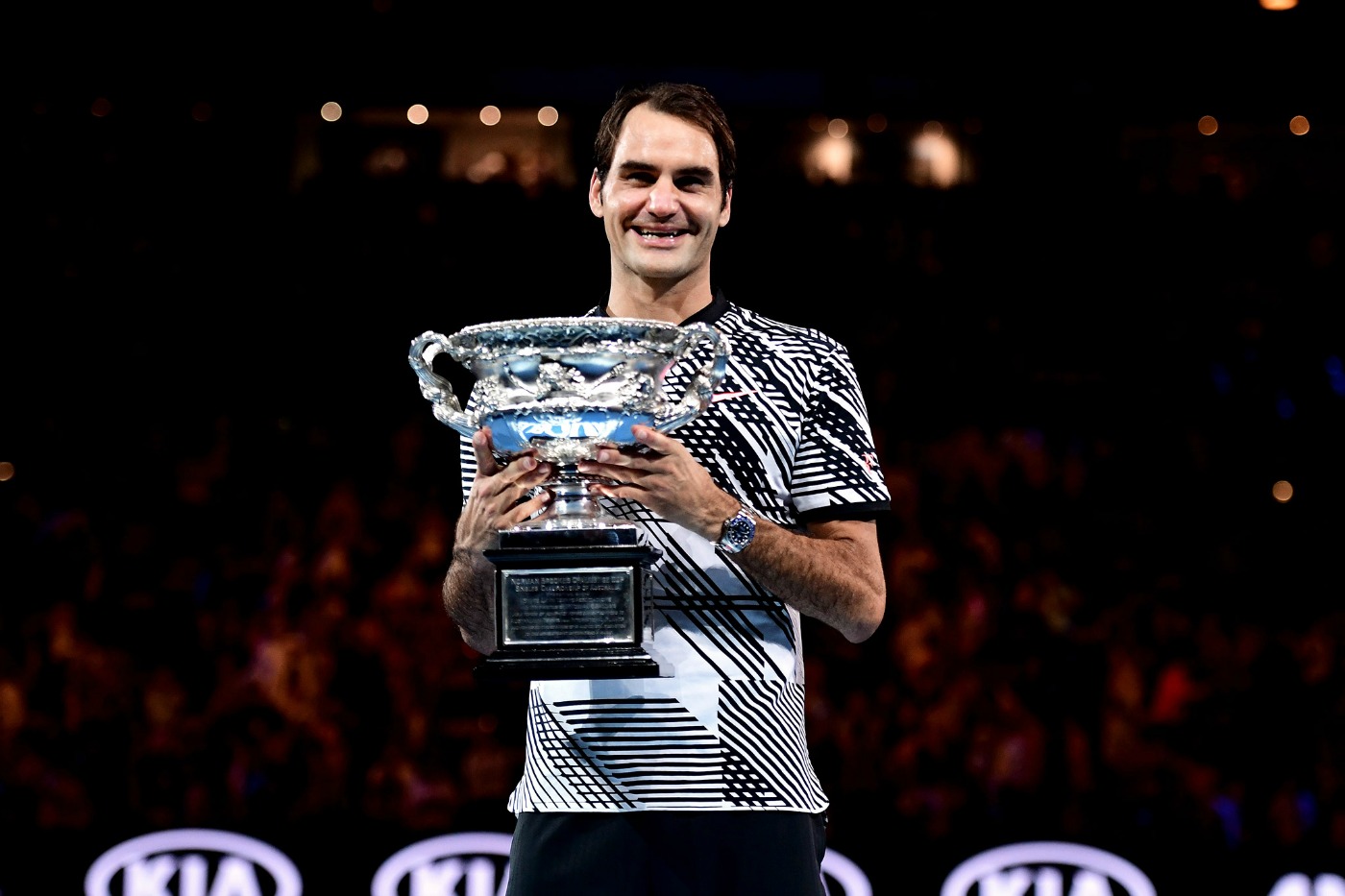

But the most noticeable difference in Federer’s game in 2017 is how fresh he has looked. In Australia, he was able to win three five-set matches over the course of a Grand Slam for the first time.

In each of them, he beat a younger opponent; and in each of them, he bounced back after losing the fourth set to win the fifth. Last week in Indian Wells, it wasn’t Federer’s endurance that was on display, but his springiness. In the race to get in the first strike, he beat his younger opponents to the punch every time.

Federer, in short, is rested. Before coming to Melbourne, he hadn’t played a match in seven months. Before coming to Indian Wells, he had played just two in the previous five weeks. Federer knows the value of that rest at this stage of his career, and has vowed to get as much of it as possible in 2017.

“I want to play, if people see me, that they see the real me and a guy who is so excited that he’s there,” he said in Indian Wells. “So that’s a promise I made to myself that if I play tourmaments that’s how my mindset has to be.”

After a pause, though, Federer added one more thought.

“So yeah, we’ll see after Miami.”

In those words lies his dilemma. He wants to play only when he’s fresh, but that’s not how the tour is designed. The majors last for two weeks, obviously, and there are three sets of back-to-back Masters 1000 events.

Indian Wells-Miami is the first of them, and Federer initially seemed torn about entering both. But after he played so well in the first one, how could he pass up the second?

The question may become more difficult during the clay-court season, which is the most physically taxing stretch of the season.

Still, questions of schedule and ranking can come later; they don’t capture what has made this comeback by Federer a special one so far.

He walked in a champion, he leaves a champion.@rogerfederer earns a 5th #IndianWells to tie Novak Djokovic w/ tournament record #BNPPO17 pic.twitter.com/s7AocAaRNE

— BNP Paribas Open (@BNPPARIBASOPEN) March 19, 2017

In adding to his game and winning the Australian Open and Indian Wells, Federer has done more than merely play great tennis. He has reversed the standard narrative of the aging athlete. This time, maybe for the first time, it’s not about what a 35-year-old can no longer do on a tennis court. It’s what about what a 35-year-old — or any person of any age — can still discover in himself.